Table of Contents

CKD is under-recognized as a disease and as a disease multiplier. The following overviews the consequences of both, along with guideline-driven tests and management tools that can help improve patient outcomes and mitigate costs.

Prevalence and cost

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) remains a largely under-recognized and growing public health issue. Nearly 90% of the estimated 37 million U.S. adults with CKD remain unaware of their condition.(12) Health inequity continues to manifest itself as a disproportionate prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and CKD in communities of color and other socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. These same individuals also have lower access to nephrology care, home dialysis, and kidney transplant.(13,14)

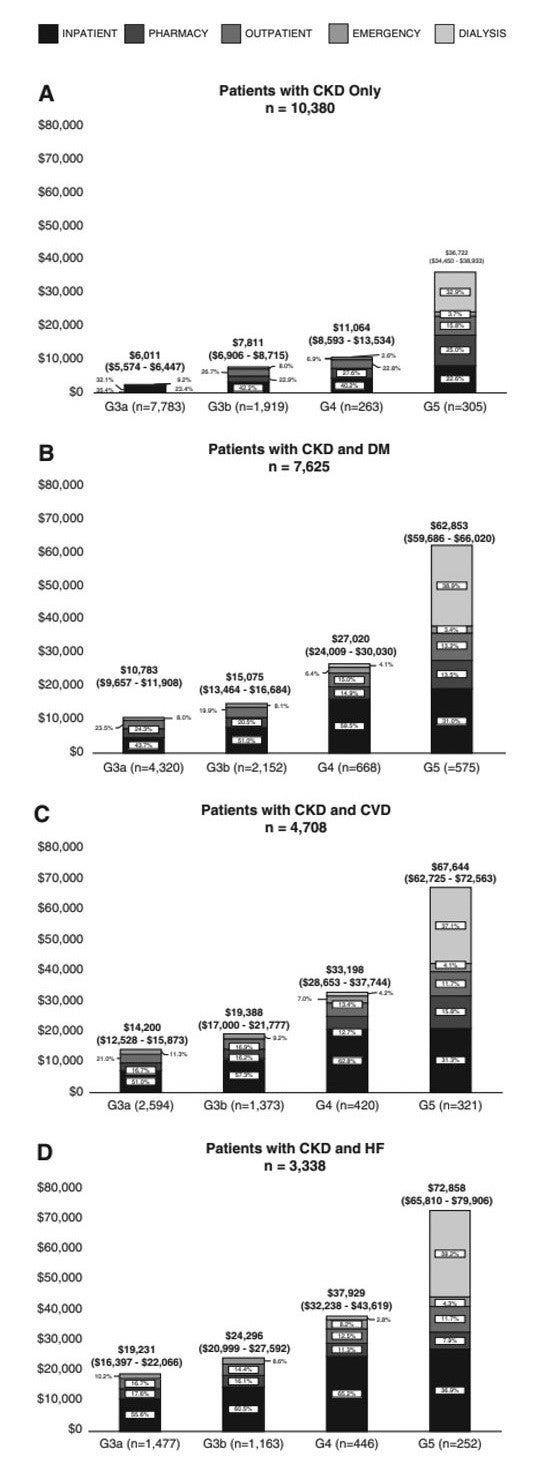

Inertia in earlier CKD recognition and management exacerbates CKD as a disease multiplier, often leading to heart failure, coronary artery disease and premature cardiovascular death.(15,16) In fact, nearly 50% of patients with CKD die from cardiovascular disease before reaching end-stage renal disease.(15,16) Earlier identification and intervention provide opportunities to prevent or slow CKD progression, thereby improving outcomes and mitigating health care costs associated with cardiovascular disease and events. For patients with CKD and cardiovascular disease, annualized mean medical costs (inpatient, pharmacy, outpatient, emergency, and dialysis) have been estimated to range from $14,200 in Stage G3a to $67,644 in Stage G5. In patients with CKD and heart failure, annualized mean medical costs increase from $19,231 in Stage G3a to $72,858 in Stage G5.(17)

Health care costs by type of expenditure across eGFR stages among patients with and without diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and heart failure.

CKD Diagnosis and Management

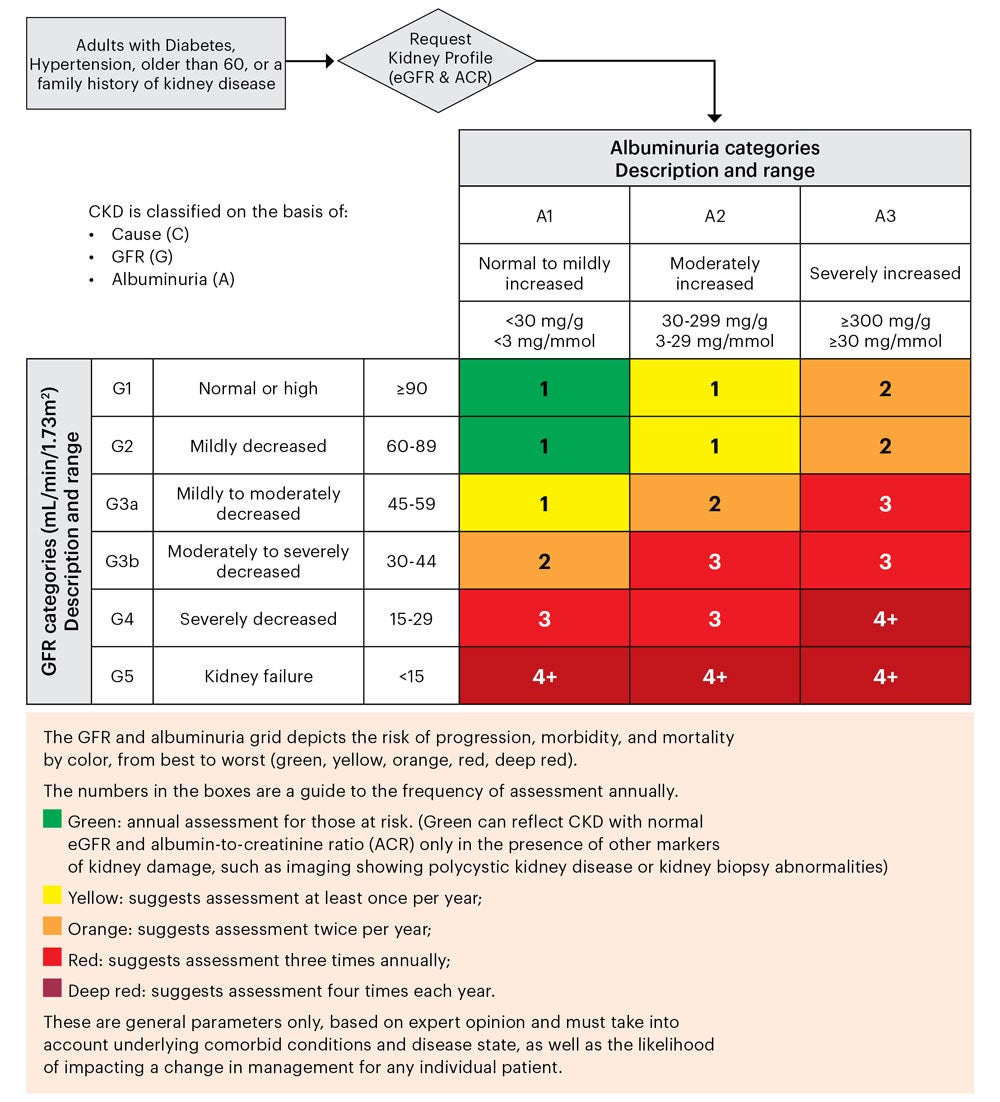

Two guideline concordant tests are used to assess CKD: glomerular filtration rate estimated from serum creatinine concentration (eGFR) utilizing the 2021 CKD-EPI 2021 race-free eGFR algorithm and urine albumin-creatinine ratio (uACR). CKD is defined as the presence of eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 and/or markers of kidney damage present for three months or more.(18) The primary marker of kidney damage is the uACR > 30 mg/g. In clinical practice the most common tests for CKD include eGFR and uACR, and those at highest risk for CKD—persons with diabetes and/or hypertension—should be tested at least annually.(18,19)

Management includes reducing the risk for progression and risk of associated complications such as cardiovascular disease, acute kidney injury (AKI), CKD anemia, CKD metabolic acidosis, as well as CKD mineral and bone disorder.

Prevention of CKD progression and cardiovascular risk reduction requires patient-specific considerations including:

- Setting blood pressure goals(20,21,22,23)

- Hemoglobin A1c targets(24,25)

- Use of medications (widely accepted/used ACEs, ARBs and statins as well as novel therapies such as non-steroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (ns-MRA), Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists). When prescribing medications, the level of estimated glomerular filtration rate should be considered to reduce patient safety hazards, and prolonged use nephrotoxins such as of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should generally be avoided.(26,27)

- Referral for medical nutrition therapy(28,29)

- Key considerations for referral to nephrology specialists include an eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2, severe albuminuria (uACR > 300mg/g), undetermined CKD etiology and acute kidney injury.(30,31)

Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease Progression and Frequency of Assessment

(according to estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR))

References

- 12. Alfego D, Ennis J, Gillespie B et al. Chronic kidney disease testing among at-risk adults in the U.S. remains low: real-world evidence from a national laboratory database. Diabetes Care. 2021 Sept;44(9):2025-2032.

- 13. United States Renal Data System. www.usrds.org

- 14. CDC CKD Surveillance System. https://nccd.cdc.gov/CKD/

- 15. Jankowski J, Floege J, Fliser D et al. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease: pathophysiological insights and therapeutic options. Circulation. 2021 Mar 16;143(11):1157-1172.

- 16. Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 2004 Sep 23;351(13):1296-305.

- 17. Nichols GA, Ustyugova A, Anouk DL et al. Health care costs by type of expenditure across eGFR stages among patients with and without diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and heart failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020 Jul;31(7):1594–1601.

- 18. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI Clinical practice guide- lines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;39:S1-S26.

- 19. Vassalotti JA, Centor, Turner BJ et al. Practical approach to detection and management of chronic kidney disease for the primary care clinician. Am J Med 2016 Feb;129(2):153-162.e7.

- 20. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/ AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guide- line for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and manage- ment of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2018; 71(6): p. e13-e115.

- 21. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206-1252.

- 22. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL et al., 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth joint national committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014. 311(5):507-520.

- 23. Taler SJ, Agarwal R, Bakris GL et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for Management of Blood Pressure in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(2):201-213.

- 24. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes and CKD: 2012 Update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012 Nov;60(5):850-86.

- 25. Inker LA, Astor BC, Fox CH et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(5):713-735.

- 26. Friedewald, V.E., Bennett JS, Christo JP et al. Editor’s consensus: selective and nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cardiovascular risk. Am J of Cardiol, 2010. 106(6):873-884.

- 27. Leonard CE, Freeman CP, Newcomb CW et al., Proton pump inhibitors and traditional nonsteroidal anti-inflam matory drugs and the risk of acute interstitial nephritis and acute kidney injury. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 2012. 21(11):1155-1172.

- 28. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice Guideline. https:// www.andeal.org/files/files/CKD/CKD2020_Comparison_ Table_20200820.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2023.

- 29. Kramer H, Jimenez EY, Brommage D et al. Medical nutri- tion therapy for patients with non-dialysis dependent chronic kidney disease: barriers and solutions. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018 Oct;118(10):1958-1965.

- 30. Chan MR, Dall AT, Fletcher KE, et al. Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease Referred Late to Nephrologists: A Meta-analysis. Am J Med 2007;120:1063-70.e2.

- 31. Vassalotti JA, DeVinney R, Lukasik S et al. CKD quality improvement intervention with PCMH integration: health plan results. Am J Manag Care. 2019 Nov 1;25(11):e326-e333.