February 06, 2026

By Joseph Vassalotti, Chief Medical Officer, National Kidney Foundation

This new blog series is authored by physicians and researchers committed to improving kidney health through evidence-based care, collaboration, and early detection. We aim to bridge the gap between research, guidelines, real-world practice, examining what we know, and how care is delivered to patients. References and resources are provided in the hyperlinks.

After the Super Bowl LX television commercial featuring Octavia Spencer and Sofía Vergara promoting the mission to learn about uACR, this is a fitting time to reflect on albuminuria. This topic has garnered considerable attention recently in nephrology, but may be unfamiliar to millions watching on television.

This article takes a closer look at why albuminuria matters, how it’s used in real-world care, and why increasing testing could improve outcomes for millions.

Albuminuria helps identify kidney disease early in people at risk, particularly those with diabetes or hypertension (high blood pressure). It also allows clinicians to monitor disease progression and response to therapy in people with established CKD. Despite its importance in predicting both kidney and cardiovascular outcomes, rates of albuminuria testing remain low in American clinics.

An underappreciated aspect of real-world practice is who orders which urine tests. Nephrologists most commonly order urine protein–creatinine ratio (uPCR), while primary care clinicians are far more likely to assess albuminuria for both detection and monitoring of kidney diseases.

In a national laboratory study of 28 million U.S. adults with diabetes and/or hypertension but no diagnosed CKD, 68.5% of uACR tests were ordered by family medicine and internal medicine clinicians, compared with just 2.5% by nephrologists. In contrast, nephrology accounted for 54.3% of uPCR testing, versus 24.8% from primary care.

Importantly, uACR and uPCR are different tests that provide distinct information. There is a rationale for using both tests, particularly as part of an initial evaluation for the detection of non-albumin protein for the diagnosis of tubular disorders and disorders of urinary paraproteins. So, why all the fuss about albuminuria?

In the early 2000s, nephrology lagged far behind other specialties in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). A 2004 study showed nephrology had the fewest RCTs among the thirteen disciplines of internal medicine. Moreover, an analysis of RCTs two years later showed people with CKD were frequently excluded, and albuminuria was not assessed in cardiovascular trials. Over the last two decades, the evidence supporting albuminuria testing has steadily expanded, spanning an accrual of epidemiologic studies that confirmed the CKD definition and risk stratification or heat map classification, including the development of kidney and cardiovascular outcome prediction models, and publishing both primary and secondary endpoints in seminal contemporary RCTs of kidney- and cardiovascular-protective therapies (CREDENCE, CONFIDENCE, DAPA-CKD, EMPA-KIDNEY, FIDELIO, FIGARO, FINE-ONE, FLOW, and others). A repeat analysis comparing RCTs across specialties would be methodologically changing to conduct today, with many contemporary trials capturing both cardiovascular and kidney outcomes.

In collaboration with regulatory agencies, National Kidney Foundation (NKF) established a 30% reduction in albuminuria as a therapeutic marker in RCTs. Consistent with this, the American Diabetes Association recommends a ≥30% reduction in albuminuria as a treatment target in diabetes when uACR exceeds 300 mg/g.

Policy and quality initiatives are reinforcing these advances. The NKF has incorporated albuminuria testing into the Kidney Health Evaluation (KHE) HEDIS measure for commercial insurance and into Medicare and Medicaid quality programs among Americans with diabetes. Supported by the recent ACC/AHA hypertension clinical practice guideline, the NKF is working to expand the KHE measure to include hypertension in addition to diabetes.

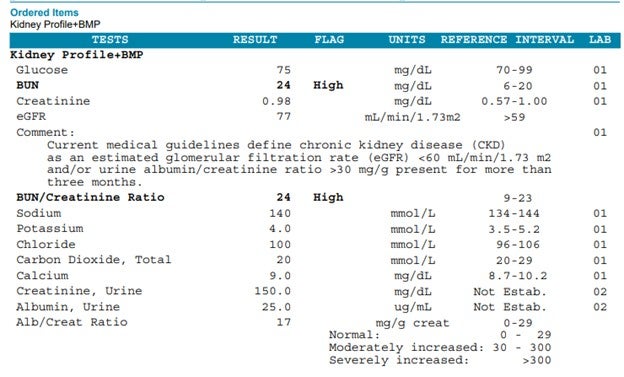

On the laboratory front, the NKF Laboratory Engagement Initiative has promoted standardized uACR testing with reporting in mg/g, eliminating the microalbumin term. Major U.S. laboratories now offer a kidney profile combining eGFR with uACR, simplifying ordering and reporting format. See the example from LabCorp shown together with the basic metabolic panel.

More recently, the NKF convened the Measurement of Urinary Proteins in Clinical Trials and Clinical Practice conference, which evaluated uACR and uPCR, demonstrating that albuminuria is preferred because assays will be internationally standardized by 2027, pre-analytical handling and sampling are well defined, and albumin concentration is more strongly associated with clinical outcomes than urinary total protein, especially in high-risk individuals.

Best practices emphasized first-morning samples for albuminuria confirmation and avoiding testing during symptomatic urinary tract infection, febrile illness, or 24-hours after vigorous exercise. Implementation initiatives such as NKF’s CKDintercept have embedded systematic albuminuria testing through health-system leadership engagement, data mining for registry function, and practice transformation as described in the NKF CKD Change Package.

For people living with kidney disease, NKF offers kidney clips to help people living with kidney diseases understand the heat map risk classification, including what can be done for kidney health. Unlike eGFR, which typically stabilizes in response to effective therapies, uACR improvement with the array of pharmacologic kidney- and cardiovascular protective pillars and lifestyle modification therapies makes albuminuria trending more hopeful for people living with kidney diseases.

Let’s work to increase albuminuria testing among practitioners as well as establish the nephrologist to lead in promoting the use and interpretation of the test along with primary care and other colleagues.