May 29, 2025

Pulitzer winner Maura Casey’s memoir shares her sister’s battle with kidney failure in the 1960s. Learn more.

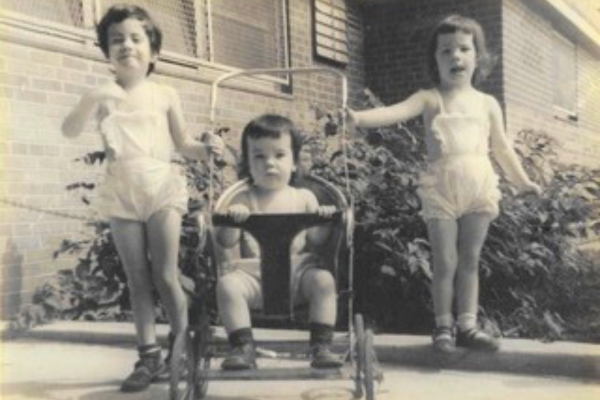

Siblings Kate (L), Maura, and Ellen (R).

Maura Casey began journaling as a child, a habit that sparked an award-winning journalism career. Her investigative work, which exposed serious flaws in the Massachusetts prison system, earned her a 1988 Pulitzer Prize for General News Reporting. She later served on the editorial board of The New York Times and received the prestigious Pulliam Editorial Fellowship, given to just one editorial writer in the nation a year.

It wasn't until the COVID1-19 lockdown that Maura turned inward to write her most personal story yet: a memoir about her sister's fight to survive kidney failure in the 1960s–a time when transplantation was rare and hope even rarer.

Finding the Story

Listen to "A Legacy of Hope with Maura Casey" on Spotify or Apple Podcasts.

Maura found a new project to pass the time when the world shut down.

"I found all the journals I wrote as a child and teen. I read them for the first time in 50 years," Maura said. "They detailed my older sister Ellen's fight with kidney disease during a time when transplantation was as new and exciting as walking on the moon."

Maura was intrigued as her diaries brought back memories long forgotten.

"I wrote down everything–including the wild things my mother used to say," said Maura. "The story was funny and touching, so I decided to write a memoir."

But there were still aspects of the story Maura needed help filling in. She contacted one of Ellen's doctors, Dr. Mary Hawking, Stephen Hawking's sister.

"She remembered Ellen and our family. She filled me in on all the medical details that I didn't have access to," Maura said. "She made it easy to write Saving Ellen: A Memoir of Hope and Recovery."

Now, Maura is sharing her family’s story in the hopes of helping others feel less alone in their battle with kidney disease.

Going Back in Time

Maura was eight years old when her sister got sick.

"We watched Ellen, this loud, athletic girl, slow down like a wind-up toy," said Maura. "After many doctor visits and months spent in and out of the hospital, my mother demanded answers from the pediatrician."

In 1963, Ellen was diagnosed with glomerulonephritis, or inflammation and scarring of the blood filters (glomeruli).

"The doctor told my mother that Ellen wouldn't live to adulthood. She had more children and should be grateful for them," Maura said. "All they could do was slow down the inevitable."

Maura's parents reacted differently to the news. Her father turned to alcohol and started an affair with a woman who lived nearby. Her mother told the children to fight through the pain as she focused on finding a solution that would save Ellen's life.

"My father's drinking was out of control. My mom didn't want us to share family business with others. We had to rely on ourselves," said Maura. "It was a rickety structure with no resources available to us at the time; no donor network, transplant social workers, or support groups."

Subscribe today!

Join the NKF Blog Newsletter

Get inspirational stories and kidney disease resources delivered to your inbox every month. You'll gain practical insights and expert advice to help you better understand and manage your kidney health, no matter where you are on your kidney journey.

Refusing to Take No for an Answer

Ellen (L) and Maura (R)

The family's life revolved around Ellen's ups and downs in the years that followed.

"The doctors tried every treatment available to maintain kidney function,” Maura said. "When she had a good day, we had a good day. When she was in the hospital, we were thrown into a crisis again."

Then, in 1967, Ellen's condition worsened. She had to start dialysis.

"Mom wanted to get her a transplant," Maura said. "But the only way to get a deceased donor kidney was to call every single hospital individually. Our state, New York, had 400 hospitals."

Laws also made it illegal to transport organs across state lines, making it more difficult to find a match for Ellen.

"Since a deceased donor seemed unlikely, my mom fought for a living kidney donation," Maura said. "The entire family was tested–even me, although the law back then made it so we'd need a court order for anyone under 21 to donate."

Maura, her mother, brother, and sister had O-positive blood. Back then, this was the gold standard for kidney donation. Today, kidney-paired exchange programs allow two or more pairs of recipients to 'swap' donors if they don't match.

"I was too young to donate and was mostly tested to feel included," Maura said. "Mom said my brother couldn't do it because of athletics, and my sister couldn't do it because it might interfere with having children."

Dr. Hawking assured them that kidney donation was safe for Maura's elder siblings. It would not affect athleticism or fertility.

"The surgery would not be safe for my mom, who had a heart murmur and was a lifelong smoker. She would have been denied today, but rules were different back then," Maura said. "We couldn't change her mind."

Interested in living kidney donation or transplantation? Watch videos by patients and living donors to learn more.

Saving Ellen

In 1970, doctors agreed to save Ellen's life at the risk of her mother's.

"Before Ellen got sick, she had glowing skin and beautiful reddish hair," Maura said. "Now she was gray and looked frail, almost like a wraith. She was dying."

But Ellen came back to life within half an hour after getting her new kidney.

"What struck me right away were her rosy cheeks—something I hadn't seen in years," Maura said. "She was vibrant and beautiful again. It was a thrill."

Maura's mother, on the other hand, did not do as well.

"My mother's remaining kidney stopped working for a few days," Maura said. "They were just about to start her on dialysis when her kidney, like an old motor in the dead of winter, finally chugged back to life."

The family and healthcare team breathed a sigh of relief. "We thought they were going to switch places," Maura explained.

While Ellen got her second chance at life, it wasn't without complications.

"The only way to fight rejection then was with massive doses of steroids," Maura said. "Ellen had horrible side effects and immediately developed steroid-induced diabetes."

Today, Ellen would have taken immunosuppressant medications. While they have side effects, they are less extreme than high-dose steroids.

"Steroids were considered a breakthrough," Maura explained, "Before them, doctors used full-body radiation to kill enough white blood cells to prevent rejection. This was much more harmful to the patient."

As Dr. Mary Harking told Maura, "Steroids were the only choice. It would have devastated everyone if Ellen’s body rejected the kidney."

Despite the difficulties, Ellen was thrilled to start living life to the fullest again.

"She went on to go to college, join a rowing team, and have a career in medicine studying infant brainwaves," Maura said. "It was a miracle. Had Ellen gotten sick 10 years before, she would have died in childhood."

Bittersweet Endings

Time passed, and life went back to normal, but no one ever forgot about Ellen's transplant.

"One of my sisters joined the military, and another became a lawyer. My brother became a surveyor and I became a journalist," Maura said. "Through it all, we donated blood frequently. We felt responsible to give back in some way."

Unfortunately, Maura's mother passed away in her mid-fifties from health issues that worsened after her donation.

"My mom took a big risk with that transplant–one she wouldn't have had to take today," Maura said. "Regardless, as a mother, she had the right goal in mind: to save my sister. And she succeeded."

Ellen's kidney lasted for twenty years before failing–far longer than her doctors predicted. She passed away at 35, from complications related to a second transplant, but Maura is forever grateful that her mother gave Ellen that additional time.

"No one wants to go through difficult situations, but they can change you for the better. It made me a writer. It gave me the chance to educate others while preserving Ellen and my mother’s memory," Maura said. "Don't give up hope. Support is available–even if it's just an empty page. "

Don’t Face Kidney Disease Alone

No one should ever have to fight kidney disease without support. The National Kidney Foundation (NKF) is here to help. Whether you’re navigating a diagnosis, dialysis, transplant recovery, or living donation, you don’t have to go through it alone.

- NKF PEERs: Get matched with a trained mentor who’s been where you are.

- NKF Communities: Join our anonymous online kidney disease support groups.

- Contact NKF Cares: Call toll-free at 855.653.2273 or fill out an online form for 1-on-1 guidance.