June 06, 2023

Jess Walters is an independent scholar, a remarkable artist, and a fierce advocate. With a neurodivergent deaf-queer identity that fuels their drive, Jess passionately leverages their lived experiences to empower individuals with disabilities, raise awareness about social determinants of health, and promote equitable access to quality healthcare. As if that weren’t impressive enough, Jess is also recognized as a leader in their local creative community as an interdisciplinary artist creating works and cultivating opportunities that captivate the mind and inspire action.

Jess’ Alport Syndrome diagnosis

Jess captured with "Can You Lend A Hand?," their interactive ASL-themed temporary mural installation at New City Arts Initiative February 2022. Photo Credit: Kori Price

When Jess was 16, they were diagnosed with Alport Syndrome, a rare genetic disease that damages the kidneys and can lead to hearing loss or eye problems. Learn more about Alport Syndrome.

The earliest and most common symptom of Alport syndrome is hematuria (blood in the urine). People with Alport Syndrome can also have proteinuria (protein in the urine), high blood pressure and edema (swelling in the legs and around the eyes).

"When I was three years old, I had gross hematuria, which is a lot of blood in your urine," Jess said. "I was formally diagnosed with hearing loss and given hearing aids at 14. When I was 16, a pediatric nephrologist saw the proteinuria and hearing loss and said, 'I've been waiting for you.' I got the Alport diagnosis immediately because he was looking for it. He diagnosed me with the wrong type, though. Because of the lack of availability of thorough genetic testing at the time, he assumed I was autosomal recessive, though further testing with advancements in technology would later reveal that I was autosomal dominant."

If these symptoms were present so early, why did it take thirteen years to receive a diagnosis? Alport Syndrome diagnoses can be challenging for people assigned female at birth to obtain because it primarily affects those assigned male at birth since it is carried on the X chromosome. There is even an outdated notion that women and those assigned female at birth are only "carriers" who pass the disease on and therefore don't or rarely experience kidney disease and kidney failure.

"There has been a recent battle to change the language defining Alport Syndrome so that females are not represented as "carriers." It's been difficult because males typically have more prominent characteristics or outward appearances of the disease like the late onset deafness in adolescence and kidney failure," said Jess. "I was an even rarer case and wouldn't meet another person with Alport Syndrome until I was 22. All that time I'd been told that I was alone, adding to the terror of the disease."

Do you need support? You aren't alone! Talk to someone who's been there with NKF Peers, our peer mentoring program that connects kidney patients with trained mentors who have been there themselves.

Living with kidney failure and getting a transplant

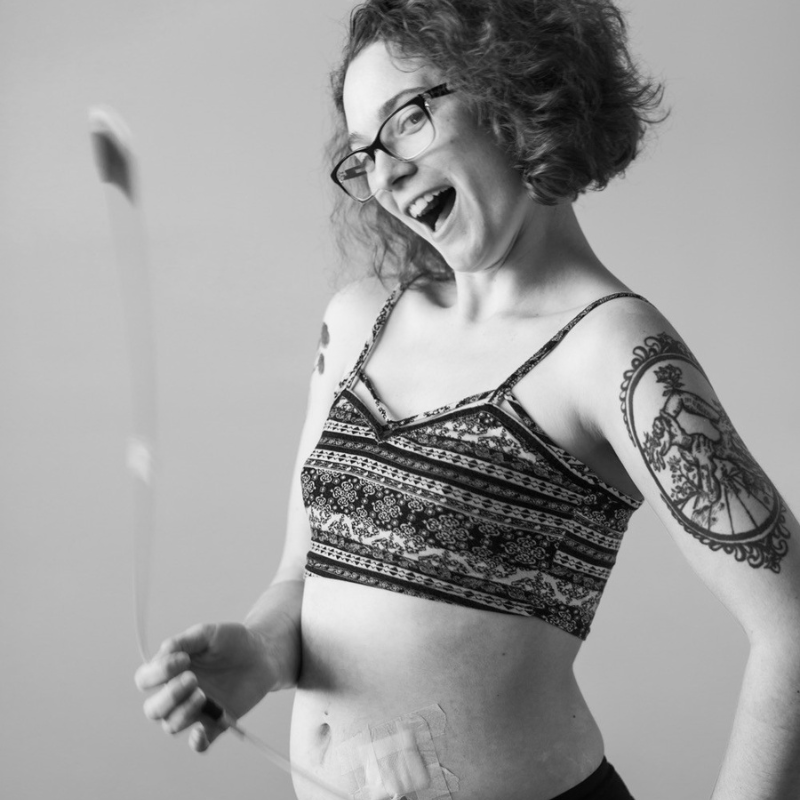

Jess with a PD catheter, September 2018. Photo Credit: John Borgquist

Toward the start of 2018, Jess participated in an observational study that used measured GFR instead of eGFR.

"With a measured GFR, you sit in a chair for at least 5 hours and they take repeated draws to get an average of your kidney function. It doesn't happen very frequently because it's costly and patients don't want to sit for that long. Ironically, I was doing my very last measured GFR session when the nurse discovered I was in stage 4," Jess said. "I think the train wreck that was my life in 2017, caused kidney failure. I was living in D.C. and had been accepted into a graduate program. Then I found out that a close family member experienced a sudden decline in health, so I deferred my full scholarship and moved back to Charlottesville to work and essentially wait for my kidneys to fail.”

Jess had their catheter placed in August 2018 and began peritoneal dialysis (PD) in October.

"I did everything in my power to have a preemptive kidney transplant, but it didn't happen because of logistics. The donor testing was taking a long time and I couldn't wait to go on dialysis any longer–I was going to the E.R. frequently and got debilitating migraines that would last for days,” said Jess. “I couldn't keep food down, had no appetite, and was asleep for three-quarters of the day. I couldn't work anymore. It was traumatic."

Thankfully, Jess only had to do dialysis for a few months while waiting for their living donor to finish the living donor evaluation process. Sign up for Becoming a Living Donor, an online, self-paced class that teaches you everything you need to know about living donation.

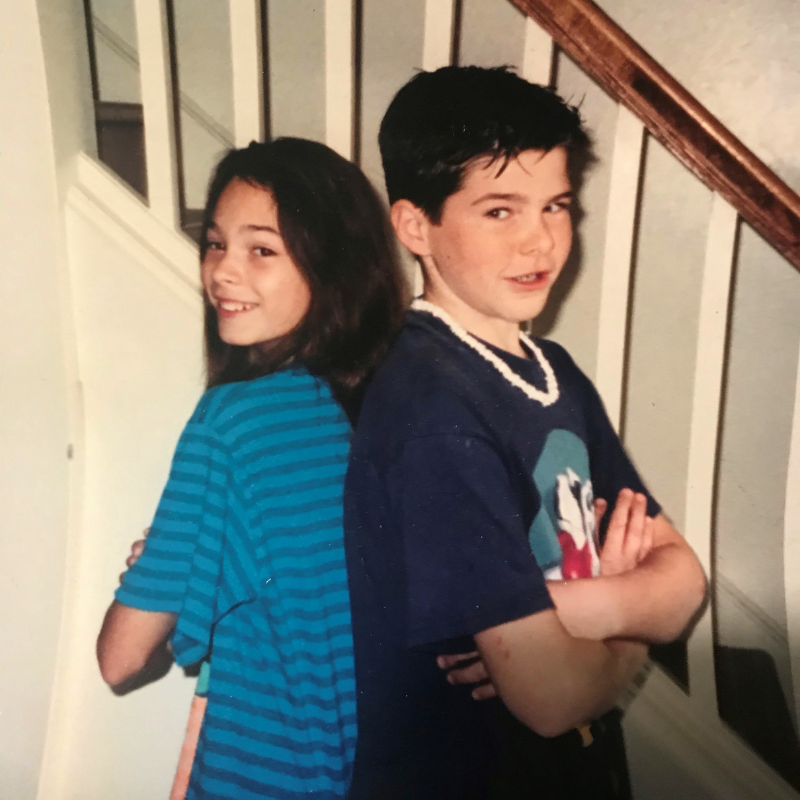

Jess (Left) and Charles (Right) in 1998-9

"I grew up with Charles, my living donor. Our mothers worked on the same aircraft in the Air Force and were best friends. He was one of the first people to step up and it was uncanny how we knew it would work out before the tests even came back," Jess said. "He's a public school teacher, so we did the transplant surgery over Christmas break, which I don't recommend since the holidays don't make doctors very accessible. I even had our surgeries filmed for my upcoming documentary The Art of Our Scars. Both of us recovered incredibly well and quickly."

After this life-changing surgery, Jess began exploring their gender identity.

"When I came back after my transplant, I was aware of being in an egg state, which is when you don't know you’re trans yet and figuring it out. I knew something was different but couldn't put my finger on it. I'm still exploring but I'm comfortable with the queer nonbinary identity,” Jess said. “If how we perceive gender and sex in science didn't rely on the binary, I may not have been misdiagnosed and had access to drugs that could have protected my kidneys.”

Learn more about the impact of unequal care for LGBTQ+ kidney patients.

Creating art and advocating

Jess in the Senate office building during the 2023 NKF Patient Summit. Photo Credit: Ian Walters

Jess's advocacy is far-reaching. They were an inaugural member of the Emerging Leadership Council for the Alport Syndrome Foundation, serves as a Voices for Kidney Health Advocate, and volunteers with several other nonprofit organizations related to kidney health, autism, and art. They’ve attended Kidney Patient Summits and serve on the DEI board of the Kidney Advocacy Committee, where they ensure NKF is equitably advocating for all people. Jess was also part of the 2021 NKF/ASN Task Force on Reassessing the Inclusion of Race in Diagnosing Kidney Diseases, giving testimony in support of the efforts to remove race-based eGFR calculations.

Learn more about NKF’s advocacy efforts.

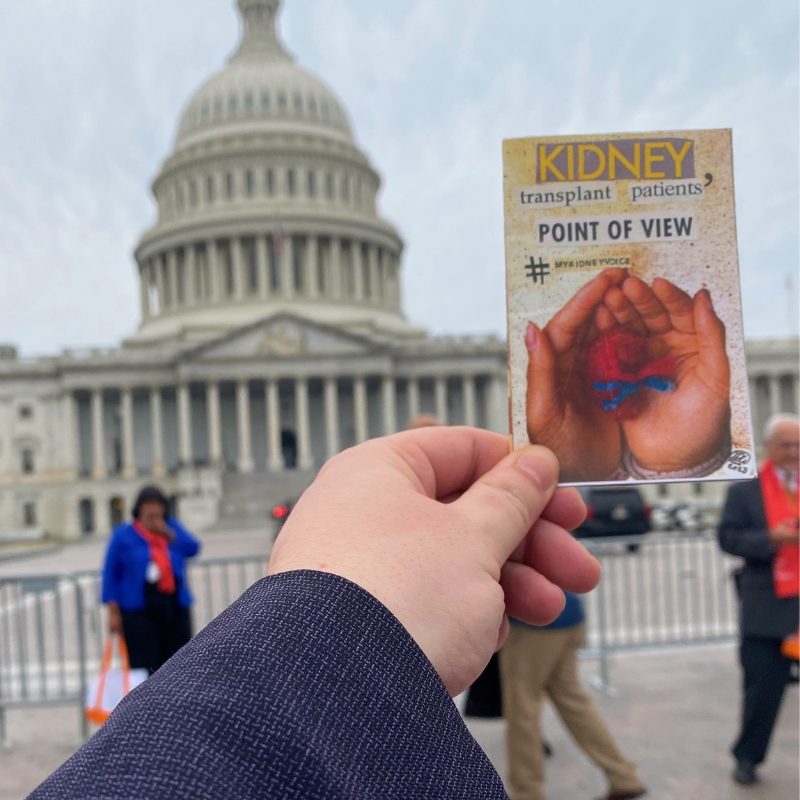

Jess holding their self-published 8-page zine "Kidney Transplant Patient's POV" in front of the U.S. Capitol for the 2023 NKF Patient Summit. The zine was distributed to staffers in each meeting with extra copies intended for representatives.

"Medical literacy is very important to me. I am one of the small percentages of people who had access to peritoneal dialysis in lieu of hemodialysis. I know people who are actively engaging with dialysis who don’t know what PD is because they were never given the option to do it. The inequities that exist when accessing PD is a big one so I decided to show people what PD was,” Jess said. “I modeled for drawing classes with my PD equipment and I did a burlesque performance with it because there are so many stigmas around disability and infantilization of people who have catheters, ostomy bags, or are visibly disabled."

When Jess isn’t working to improve medical literacy, they are sharing the joys of sign language.

"I'm one of few Alport Syndrome patients who culturally identifies as Deaf so I learned sign language and try to give back to the community by increasing the visibility of ASL through my art and by using my platforms to advocate for ASL interpreters and other accessibility accommodations to increase engagement with the d/Deaf/Hoh community. Deaf culture was a victim of history via the 1880 Conference in Milan1 where institutional educators voted to ban sign language to the point where all people who were deaf or hard of hearing were tortured or punished if caught using sign language," Jess said. "I’ve studied disability justice and work to remove barriers to access while using my personal experiences with language deprivation to explain how amplification devices like hearing aids are a tool, not a cure."

Jess also creates artwork to uplift and bring visibility to disability and is currently working on The Art of Our Scars, a short documentary film highlighting their experience with kidney disease and transplantation.

Artwork by Jess: "Love Can Be Felt," 2022. Photograph of a Lupus patient's hands holding a felted kidney sculpture by Jess.

"I look for opportunities to use my story as a platform to share information about barriers to healthcare access, especially organ donation. The film will be short and accessible on my website, jesswaltersart.com. I’ll also screen it in places like community centers where everyone will be able to watch it," Jess said. "Ultimately, my film is a Trojan horse to talk about systemic inequities, give information about resources, and teach people about the leading causes of kidney disease. I got this transplant due to a wealth of privilege and feel it is my moral obligation to use this bonus time to make people understand some of these larger frameworks."

Big victories are possible with your voice–Become a Voices for Kidney Health advocate today.

Sources

1Moores, Donald F. "Partners in Progress: The 21st International Congress on Education of the Deaf and the Repudiation of the 1880 Congress of Milan." American Annals of the Deaf, vol. 155 no. 3, 2010, p. 309-310. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/aad.2010.0016